Sunday, April 25, 2010

Sunday, April 18, 2010

What Does "Pro-Life" Mean Anyway?

Over the past several decades, a great deal of political rhetoric has been focused on the often heated debate between those who identify themselves as “pro-life” versus those who embrace a “pro-choice” philosophy. But what does it really mean to be pro-life? Can one choose life in some circumstances but not others? Despite what many believe is a simple black-or-white, for-or-against issue, I for one struggle to decide which side I am on, or if I even need to choose a side.

As a nurse in the field of developmental disabilities, over the years I have cared for countless children and adults who were born “imperfect” by society’s standards. Until relatively recently, the typical advice for parents who produced a disabled child was to simply institutionalize the baby and “try again,” since the child was unlikely to survive longer than a few weeks or months anyway. Contrary to these dire predictions, however, many such children grew to adulthood despite their overwhelming physical and cognitive impairments.

I have often wondered, as a medical professional caring for these children, if perhaps we have done them a disservice by prolonging their lives. Particularly for those who are non-verbal, how can we know for sure that if given the choice, they would choose life for themselves? Or, if faced with the prospect of life in an institution, constantly undergoing painful medical procedures and hospitalizations designed simply to keep them alive, would they rather their parents had instead chosen abortion and thus spared them from a life filled with indignities? On the other hand, is it possible that these individuals are happy with their lives despite the hardships? Certainly many non-disabled people suffer serious, often prolonged, illnesses during their lifetime and still consider life well worth the trouble.

The answer, of course, is that nobody knows the answer, and this uncertainty is precisely why I find it impossible to take a firm position on either side of the abortion issue. However, if forced to make a choice, I would tend to opt for life in nearly all situations, and the reason is simple—nature has been in the business of selective abortion since the beginning of time, an advantage that trumps our meager experience as humans any day of the week. Children who are not meant to be born, won’t be—the naturally occurring process of miscarriage makes that decision for us.

If a child makes it into the world, then lacking any valid means to make a judgment call ourselves, I believe we must assume that he or she arrived here for a reason, even if our limited vision does not allow us to see it from where we currently sit.

As a nurse in the field of developmental disabilities, over the years I have cared for countless children and adults who were born “imperfect” by society’s standards. Until relatively recently, the typical advice for parents who produced a disabled child was to simply institutionalize the baby and “try again,” since the child was unlikely to survive longer than a few weeks or months anyway. Contrary to these dire predictions, however, many such children grew to adulthood despite their overwhelming physical and cognitive impairments.

I have often wondered, as a medical professional caring for these children, if perhaps we have done them a disservice by prolonging their lives. Particularly for those who are non-verbal, how can we know for sure that if given the choice, they would choose life for themselves? Or, if faced with the prospect of life in an institution, constantly undergoing painful medical procedures and hospitalizations designed simply to keep them alive, would they rather their parents had instead chosen abortion and thus spared them from a life filled with indignities? On the other hand, is it possible that these individuals are happy with their lives despite the hardships? Certainly many non-disabled people suffer serious, often prolonged, illnesses during their lifetime and still consider life well worth the trouble.

The answer, of course, is that nobody knows the answer, and this uncertainty is precisely why I find it impossible to take a firm position on either side of the abortion issue. However, if forced to make a choice, I would tend to opt for life in nearly all situations, and the reason is simple—nature has been in the business of selective abortion since the beginning of time, an advantage that trumps our meager experience as humans any day of the week. Children who are not meant to be born, won’t be—the naturally occurring process of miscarriage makes that decision for us.

If a child makes it into the world, then lacking any valid means to make a judgment call ourselves, I believe we must assume that he or she arrived here for a reason, even if our limited vision does not allow us to see it from where we currently sit.

Saturday, April 10, 2010

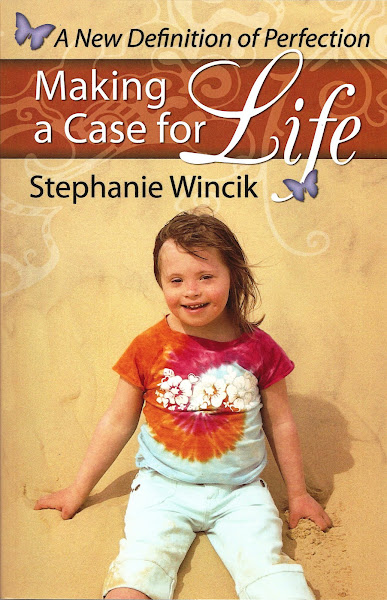

This past March 21 marked World Down Syndrome Day, an annual global event celebrating the contributions of a unique group of individuals who happened to arrive on earth with an extra chromosome. Unquestionably, people with Down syndrome make the world a better place. But if the current trend continues, fewer of us may have the opportunity to discover this for ourselves, because the Down syndrome population is being exterminated—an estimated 90% of babies expected to be born with Down syndrome are aborted.

So why is that a problem? Aren’t we really doing everyone a favor by sparing parents the heartache of producing a disabled child, as well as saving society the financial burden of supporting someone who may never even hold a job?

Ask Kurt and Margie Kondrich of Pittsburgh, whose daughter Chloe, 6, was born with Down syndrome. Chloe enjoys the life of a typical six-year-old—she attends first grade at her neighborhood school, argues with her brother, goes to birthday parties, and loves the beach. But when two of the children living next door to the Kondrichs were diagnosed with the same progressive, fatal disease, Chloe responded in a manner far beyond her years. “Chloe’s interactions with our five-year-old neighbor and his two-year-old brother are something that is not of this world,” her father says. “Her absolute unconditional love is a model for all of us…she rushes to this family who are in the darkest valley anyone could experience.”

In recent decades, life expectancy for people with Down syndrome has skyrocketed from nine years of age to roughly 60-65. But even as improved medical care is allowing people with Down syndrome to enjoy full, productive lives, 9 out of 10 Down syndrome pregnancies are terminated as a result of advanced prenatal testing methods.

Why? Because prospective parents often lack complete, accurate information about the quality of life now enjoyed by these individuals. Misconceptions about people with intellectual disabilities remain deeply ingrained in our society, particular the notion that being born with a disability is a tragedy. Contrary to this widely-held belief, studies indicate that the vast majority of families living with a person who has Down syndrome view the experience as a decidedly positive aspect of their lives.

Although a great many physicians believe that terminating fetuses with Down syndrome will result in the best outcome for all concerned, their advice is often based on outdated information or is simply the result of minimal experience and familiarity with disabled children and adults. It is this lack of personal experience, coupled with the scientific community’s giddiness over its ability to identify so-called disabilities in the womb, that has led to this silent eugenics movement.

Each year, an increasing number of individuals with Down syndrome are entering the workforce, paying taxes, and volunteering in their communities. Many are finding success as dancers, poets, actors, and filmmakers. But the most powerful impact made by persons with Down syndrome on those around them is achieved through the simple act of being themselves.

As our culture becomes ever more self-absorbed and materialistic, I believe we need more people with Down syndrome, not fewer. If we wish to reverse what appears to be a downward spiral for humanity, then tolerance, good humor, kindness, and compassion—qualities found with remarkable consistency in people with Down syndrome—are the very attributes we must hope all of the new human beings entering our world will possess. And I challenge anyone who meets Chloe Kondrich to support any argument suggesting that the world would be a better place if she had never been born.

So why is that a problem? Aren’t we really doing everyone a favor by sparing parents the heartache of producing a disabled child, as well as saving society the financial burden of supporting someone who may never even hold a job?

Ask Kurt and Margie Kondrich of Pittsburgh, whose daughter Chloe, 6, was born with Down syndrome. Chloe enjoys the life of a typical six-year-old—she attends first grade at her neighborhood school, argues with her brother, goes to birthday parties, and loves the beach. But when two of the children living next door to the Kondrichs were diagnosed with the same progressive, fatal disease, Chloe responded in a manner far beyond her years. “Chloe’s interactions with our five-year-old neighbor and his two-year-old brother are something that is not of this world,” her father says. “Her absolute unconditional love is a model for all of us…she rushes to this family who are in the darkest valley anyone could experience.”

In recent decades, life expectancy for people with Down syndrome has skyrocketed from nine years of age to roughly 60-65. But even as improved medical care is allowing people with Down syndrome to enjoy full, productive lives, 9 out of 10 Down syndrome pregnancies are terminated as a result of advanced prenatal testing methods.

Why? Because prospective parents often lack complete, accurate information about the quality of life now enjoyed by these individuals. Misconceptions about people with intellectual disabilities remain deeply ingrained in our society, particular the notion that being born with a disability is a tragedy. Contrary to this widely-held belief, studies indicate that the vast majority of families living with a person who has Down syndrome view the experience as a decidedly positive aspect of their lives.

Although a great many physicians believe that terminating fetuses with Down syndrome will result in the best outcome for all concerned, their advice is often based on outdated information or is simply the result of minimal experience and familiarity with disabled children and adults. It is this lack of personal experience, coupled with the scientific community’s giddiness over its ability to identify so-called disabilities in the womb, that has led to this silent eugenics movement.

Each year, an increasing number of individuals with Down syndrome are entering the workforce, paying taxes, and volunteering in their communities. Many are finding success as dancers, poets, actors, and filmmakers. But the most powerful impact made by persons with Down syndrome on those around them is achieved through the simple act of being themselves.

As our culture becomes ever more self-absorbed and materialistic, I believe we need more people with Down syndrome, not fewer. If we wish to reverse what appears to be a downward spiral for humanity, then tolerance, good humor, kindness, and compassion—qualities found with remarkable consistency in people with Down syndrome—are the very attributes we must hope all of the new human beings entering our world will possess. And I challenge anyone who meets Chloe Kondrich to support any argument suggesting that the world would be a better place if she had never been born.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)