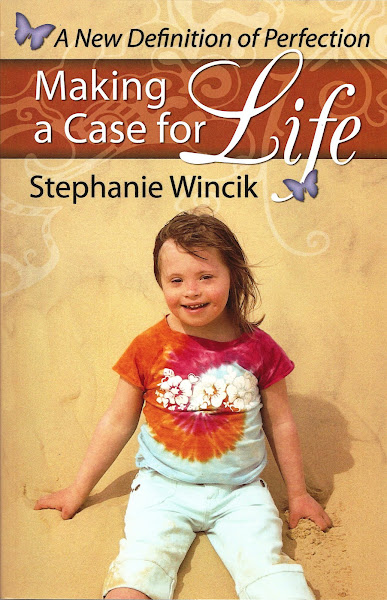

Amidst all the doom, gloom, and ongoing stress surrounding the new prenatal testing and its negative implications for people with Down syndrome, I thought it might be nice to do an uplifting post for a change. Over the past few years I've had the opportunity to speak with many individuals with Down syndrome and their families. In doing so, not only have I made some wonderful new friends, but I've observed something else rather incredible that prompted me recently to complete a second edition of my book, Making a Case for Life. The updated version, Brilliant Souls, contains a new chapter exploring the amazing connection that many people with Down syndrome appear to have with the spiritual world. What follows is an excerpt from the chapter about Chloe Kondrich, a delightful young lady from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania who, even at the tender age of nine, has already made remarkable strides as an advocate for all people with different abilities:

Amidst all the doom, gloom, and ongoing stress surrounding the new prenatal testing and its negative implications for people with Down syndrome, I thought it might be nice to do an uplifting post for a change. Over the past few years I've had the opportunity to speak with many individuals with Down syndrome and their families. In doing so, not only have I made some wonderful new friends, but I've observed something else rather incredible that prompted me recently to complete a second edition of my book, Making a Case for Life. The updated version, Brilliant Souls, contains a new chapter exploring the amazing connection that many people with Down syndrome appear to have with the spiritual world. What follows is an excerpt from the chapter about Chloe Kondrich, a delightful young lady from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania who, even at the tender age of nine, has already made remarkable strides as an advocate for all people with different abilities:In addition to her unusually loving and caring personality, over the years Kurt and his wife have noticed something else remarkable about Chloe—she seems to have a special connection to the spiritual world, and regularly reports talking to people who have passed, often describing them with astonishing accuracy. Long before Chloe’s birth, Kurt became acquainted with the Scuillo family when he was assigned to patrol their Pittsburgh neighborhood as part of his duties as a police officer. Years later, the Scuillo’s son, Paul, would follow in Kurt’s footsteps and become a police officer himself. In the spring of 2009, tragedy struck the family when Paul and two other officers were killed by a heavily armed suspect after responding to a call about a domestic disturbance.

Today, Kurt remains close with the Scuillo family and still visits Paul’s parents regularly, often taking Chloe with him. Whenever Chloe arrives at their home, Paul’s mother, Sue, notices that “she always goes straight to Paul’s picture.” Even though Paul and Chloe had never met prior to his death, Sue believes that the two frequently communicate. “Chloe tells me that she talks to Paul in her room, and sometimes she sees him in her mirror.” Any doubts Sue may have had about whether Chloe’s conversations with her son were indeed real, vanished completely during a recent visit by Chloe and Kurt. “When Chloe mentioned to me one day that Paul is with baby David, I just started to cry,” Sue says. She went on to explain that she and her husband, Max, had lost a baby to miscarriage 44 years ago—something Chloe had no way of knowing as the couple had never revealed their loss to anyone.

Sue finds great comfort in knowing that her two sons are together. Although she was convinced early on that Paul was still watching over her and her family even after passing from his physical body, Chloe’s affirmation of his continuing presence in her life has been a priceless blessing for Sue. Like others who have been touched by Chloe’s uncanny ability to reach out to others just when they need it most, Sue believes that Chloe possesses a special gift. “I know Paul is still here,” she says, “and when Chloe visits she can tell.”

Chloe’s heightened ability to connect with the spiritual world is a phenomenon that has been observed frequently in both children and adults with Down syndrome. Next, we will explore this phenomenon and its possible implications for the future of our human family.